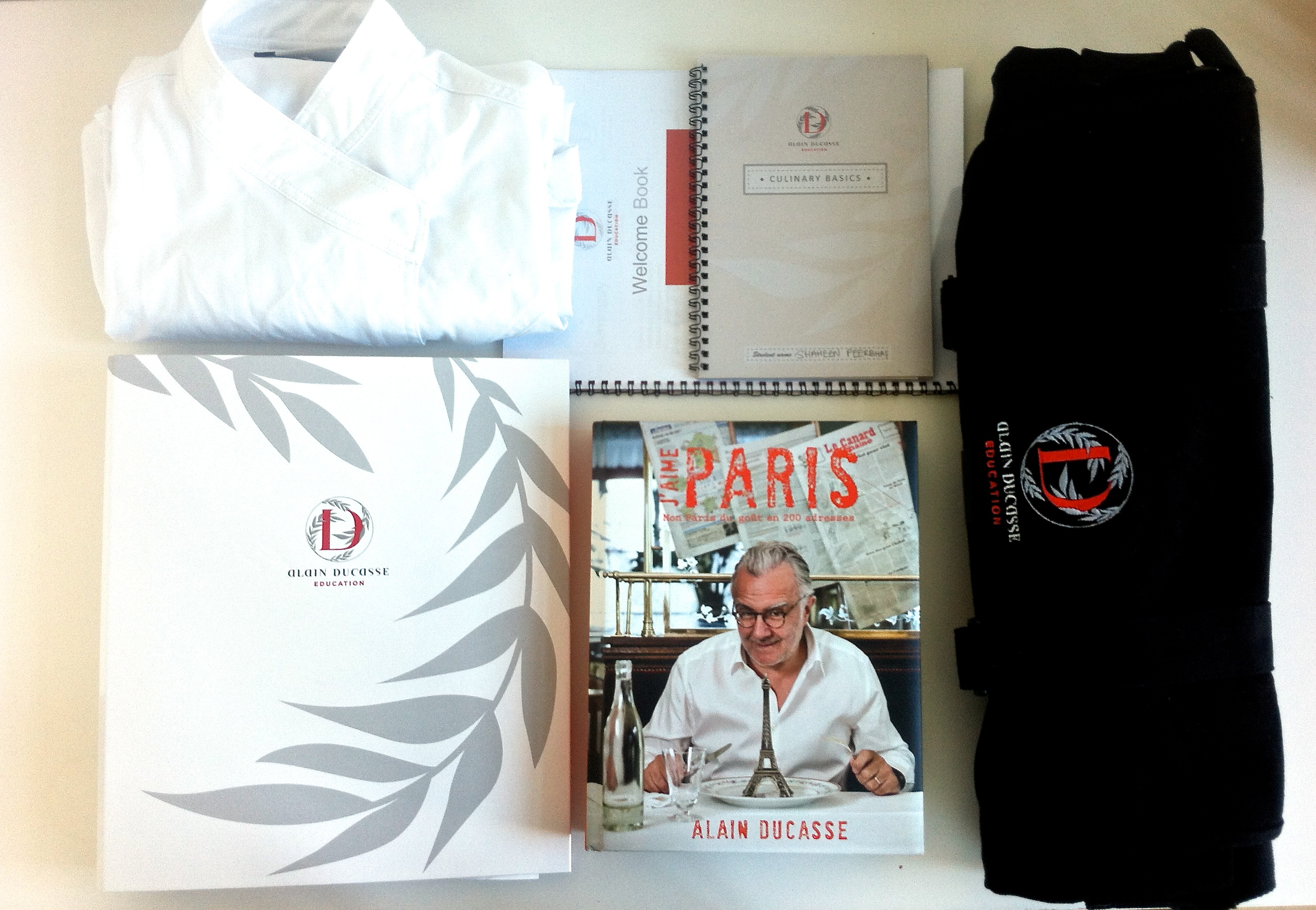

This past September, I moved back to Paris with my knives, my favourite stationery, and little else to study at Alain Ducasse Education in Argenteuil, a suburb on the outskirts of Paris. This is a result of a culinary scholarship, my fourth, granted by the James Beard Foundation.

The course is a Diploma in Superior Culinary Arts and it’s for those who are already professionally trained or have a fair amount of restaurant experience. The Alain Ducasse Centre in Argenteuil isn’t just a cooking school but a research and consulting centre. This means that everything at the school is quite dynamic and up with the times. It’s got to be, given the 21 Michelin stars Monsieur Ducasse holds. It’s undoubtedly one of the finest culinary institute in the world.

Three weeks have flown by and the lessons I have learned have been nothing short of spectacular. This is by far the most comprehensive and technical education I have ever received. And it’s only just begun.

We’re a batch of 9 students between 20 and 40 years old from all over the world, with varying educational and work experience. We start our day at 9AM, cook throughout the day, taking short breaks to taste each course we make. By the end of the day we are stuffed to the gills with world-class cuisine that our chefs teach us to prepare. I almost never eat dinner after; maybe a baguette here or a melon there.

Mondays are for organising the base that will be used during the rest of the week. We’ll make our stocks, pie crusts, sauces, and anything else we plan to use. The next four days are spent focusing on the week’s module.

Our course is divided into 10 modules, each lasting about a week. Each module is taught by a different chef, allowing us to learn different styles and approaches to creating and reimagining a dish.

Week 1 with Chef Roberto and Chef William was all about the basics: stocks, jus, tomato fondue, tomato confit, jellies, forcemeats. We learned to make different condiments. We made pesto, tapenade (the BEST I’ve ever eaten, and now I want this marble mortar and pestle), gribiche, rouille, béarnaise, ravigote and emulsions. We cooked two terrines, a fish soup and the famous quenelles Lyonnais. During the early part of the week, when we were just making the basics, the school interns cooked us beautifully plated meals. Alain Ducasse needs to take over all of the world’s school canteens.

Week 2 with Chef Yann was about the evolution of classical French cuisine, or “Tradition Evolution” as it was termed. The traditional recipes were handed out to us but the chef changed things up a bit to a modernise those recipes. I absolutely loved the foie gras royale and the beef cheeks. The theory class was enjoyable with blind tasting spices and ingredients. Identifying them is a lot harder when you can’t see them. Although I do think it’s got to do with familiarity as well – only the Indian and Iranian in the class could identify turmeric.

Week 3 with Chef Mark was a continuation of Tradition Evolution, but like my friend rightly said, it was more like Tradition Revolution. This Welsh chef has a strong, independent sense of cooking and he changes things up to veer away from the classical. He advocates spontaneity rather than rigidity. Some things worked for me (the use of Asian ingredients and styles, the clean plating), and some things didn’t (for me, the only way to eat a French onion soup is with beef stock and gratinated Gruyere). This week, nobody in class ate the veal kidneys – everybody loved the Asian pork chops.

Reflections

With every dish we’ve plated, I am developing a strong understanding of what styles and tastes I enjoy and what I don’t. It’s helping me build my identity on the plate. I’m one for generous portions that still look pretty and feminine (no tweezers, please). Splashing sauces all over the plate isn’t my style either – I’d rather keep things contained and have a cleaner plate.

My only problem is that as a cook I find it hard to properly gauge taste after a point because we’ve been smelling, eyeing, and tasting the food all day. I am usually very opinionated, but these surroundings sometimes make evaluation harder. The three best dishes we’ve made so far, in my opinion, have been the beef cheeks cooked slowly for hours, the foie gras royale and chef Mark’s Asian inspired chops with a Laos-style salad that I took seconds of.

I also find that while cooking sous-vide with a probe stuck inside gives precise results, it’s the bane of a being a good cook. When you rely so much on science and precision, you don’t cultivate the art. It’s very useful to know that these tools exist but I’m a bit old school – I want to learn to cook based on how something feels rather than depend entirely on a probe. That’s not to say I won’t use one (the Thermapen is on my wishlist), but I’d rather reduce dependence on rigorous measurements as I learn.

Next week, week 4, is all about sous-vide cooking in Torcy. Perhaps this will change my mind.

PS: Follow me on Instagram to keep up with everyday life in the kitchen and around Paris.